Figure 1: Andrea del Verrocchio, Bargello Relief, late 1400’s, Bargello Museum, Florence.

The Bargello Relief represents one of the most harrowing and realistic depictions of the realities of childbirth in art (Fig. 1). Located in the Bargello Museum, Florence, the relief depicts two separate scenes; a woman dying during the process of childbirth surrounded by grieving female attendants is portrayed on the right with the presentation of the deceased baby by the midwife to his father and a group of onlookers represented on the left.

The piece was commissioned by Giovanni Tornabuoni (the father-in-law of Giovanna degli Albizzi whose portrait I looked at in a previous blog post). Giovanni ordered the creation of this work to commemorate the death of his beloved wife Francesca Pitti who died in labour on September 23rd 1477. The relief in fact may have been a component of a much larger sculptural piece, a tomb executed by Andrea del Verrocchio and dedicated to Francesca located in the Church of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva, Rome (where Giovanni worked as the head of the Medici bank). Unfortunately, the tomb has been dismantled and lost with the Bargello relief the sole surviving piece of the work. The creator of the relief has been the subject of much debate with two of the leading Verrocchio scholars, Butterfield and Covi, attributing it to Francesco di Simone, a Florentine sculptor who worked with Verrocchio.[1] Verrocchio himself designed and executed the most important elements of the commission and assigned artists present in his workshop to assist him in the decoration.

At first glance, the relief appears to have been designed within the traditional format used for birth iconography; the depiction of the ‘lying-in scene’ (depicting the birth of a child) and the portrayal of the presentation of the child to the father for naming.[2] This scene realistically portrays the event which took place within the feminine and private realm of the birth chamber. Verrocchio graphically depicts the apparent dangers associated with childbirth and motherhood, which were faced by all women. Traditional lying-in scenes commonly found on birth trays such as Masaccio’s 1425 Desco da Parto (Fig.2) represented the ideal situation and outcome for this process, namely the successful birth of the child (preferably a boy) and the survival of the mother.

Figure 2: Masaccio, Desco da Parto, 1425-28, Gemaldegalerie, Berlin.

These trays and the illustrations adorning them were believed to possess talismanic properties, acting to protect and reassure the expectant mother at a time when death in childbirth was a common occurrence.[3] The Bargello relief depicts the opposite of these protective scenes. Kisler argues that the authenticity invested by the artist by the sculptor allowed contemporary women to read through the deceased woman’s body, sympathetically in the image and physically and emotionally through their own experiences of birth.[4] From a feminine perspective, the truthful representation of Francesca’s demise in this commemorative piece publicly validated and highlighted the risks women undertook to provide male heirs for their husbands and for the republic.

Eight grieving women surround the free-standing bed where Francesca lies. She is physically held up by one attendant whose right hand touches the deceased’s breast in the traditional position of a birth assistant. The midwife holds the other arm and searches for a pulse.[5] The women display their grief in a variety of ways; one sits hunched over in front of the bed holding her head in her hands while the woman on the far right pulls her hair in anguish.

Their collective declaration of sadness contrasts sharply to the austere and somewhat restrained expressions of the figures in the presentation scene. The articulation of suffering was customary among Florentine women when a death occurred.[6] They grieve openly whereas when the child was presented to his father and bystanders in the more public sphere, such expressions were internalised as they would have been deemed inappropriate considering the context and environment. Within the confines of the domestic bedchamber, the women disclose their feelings over the loss of the mother and male child.

The pose of the dying figure with her serene expression differentiates to the visible expression of mourning displayed by those who surround her. Francesca’s depiction is heavily influenced by examples of classical art; she is dressed in Roman garb and lies on a bed in the all’antica style. There are a striking number of similarities between Francesca’s depiction and that of the death of Meleager. Murdered by his own mother with the aid of the goddess Diana in revenge for the slaughter of his uncles, the Death of Meleager was a popular subject matter found on ancient Roman sarcophagi (Fig. 3).

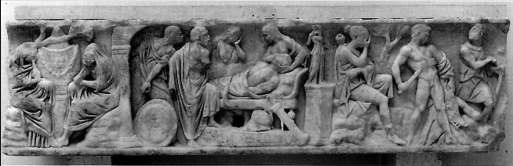

Fig. 3 Death of Meleager, 2nd Century A.D, Louvre, Paris

Traditionally, the dying hero is represented lying in state surrounded by his mourning loved ones. In both the Bargello Relief and the Death of Meleager scene, the dying protagonist lies on a bed surrounded by a group of figures with varying expressions of profound melancholy including the seated female holding her head in her hands. The principal characters do not exhibit the suffering they have endured. By depicting Francesca in this manner, Verrocchio conferred the deceased with a sense of heroic dignity and gravitas. Her calm appearance masks the pain and suffering she obviously endured. It is only subtly referenced to through the depiction of her limp, tousled hair which sticks to her neck, her dress slipping down her left arm and the exposing of her left breast. The fact that she is portrayed as sitting up in the bed demonstrates how she was physically exhausted from the labour.[7]

It is interesting to note that Verrocchio chose not to depict the caesarean birth which Giovanni alludes to in a personal letter about Francesca’s death. The focus is upon the aftermath of the childbirth process, with the child swaddled and held by the wet nurse whose bodice remain tied, indicating that the child is dead, as well as Francesca’s final moments. The representation of such a traumatic and grisly procedure would have been deemed inappropriate and too graphic for this commission and its contemporary audience. The emphasis here is on Francesca’s portrayal as a courageous woman who, after suffering the agony of a failed delivery, remained dignified to the end. Her willingness to die in order to give birth to her son demonstrates her heroic nature.

Unlike typical representations of the presentation of the infant to his father for naming, Verrocchio depicts the moment when the midwife presents the dead swaddled child. Immediately, the viewer is confronted with a sense of tragedy and loss of not only the baby but also his mother. The inclusion of a clearly recognisable Giovanni (when compared to other representations of the patron, (Fig. 4) provides an insight into society’s focus upon the promotion of the patriarchal line and strength of the family. Francesca was only identifiable through her association with her husband and his portrayal in the opposite episode. Emphasis is thus placed upon the Tornabuoni lineage and Francesca’s contribution to it as the mother of the family’s sole heir.

Fig. 4. Detail of Domenico Ghirlandaio’s Donor Portrait of Giovanni Tornabuoni, 1485-1490, Tornabuoni Chapel, Santa Maria Novella, Florence.

The relief was designed to act as a didactic narrative to emphasise the role of motherhood to the female audience. Although the scene depicts her death, the implied message is a positive one as it points to the possibility of achieving a revered status through the fulfilment of their duties as patrician wives. Verrocchio chose to portray the realities of the surrounding death within the domestic context, respectful of the mourning customs of the time while simultaneously giving a truthful image of this emotional event for all those involved in the process, an event which women would experience in one capacity or another during their lives.

[1] A. Butterfield, The Sculptures of Andrea del Verrocchio, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1997, 238 and D. Covi, Andrea del Verrocchio, Life and Work, Arte e Archeologia, Studi e Documenti, 27, Leo S. Olschki Editore, Florence, 2005, 148.

[2] M. Kisler, ‘Florence and the Feminine’, in J. Levaric Smarr and D. Valentini (eds.), Italian Women and the City: Essays, Dickinson Press, Madison, NJ, Fairleigh, 2003, 70.

[3] J.M. Musacchio, ‘Imaginative Conceptions in Renaissance Italy’, in G.A. Johnson and S.F. Matthew Grieco (eds.), Picturing Women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1997, 42-60.

[4] Kisler, ‘Florence and the Feminine’, 71.

[5] Ibid, 70.

[6] S. Strocchia, Death and Ritual in Renaissance Florence, The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London, 1992, 117.

[7] Kisler, ‘Florence and the Feminine’, 71.

Dear Ms. Hoystead: Thank you for writing “The Bargello Relief- Representing the Realities of the Renaissance Birth Chamber.” This is a wonderfully informative entry. This Spring 2017 I am assigning it for the students in my class (ENL 4230 & LIT 5934) at the Univ. of North Florida (in Jacksonville, FL) to look at and read. This is a course on Disability Studies in the Humanities. I also quote a sentence from it in a book I am writing. In case you want to contact me, you can best reach me through this email: cgabbard@unf.edu. All best to you! Prof. Chris Gabbard

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] of his wife and baby to his nephew, Lorenzo the Magnificent. (For more on this relief, please read this illuminating post by Elaine Hoysted on the blog “Renaissance […]

LikeLike

Thank you this is really interesting, and I thought profoundly moving. It will be great for my students to read as we are about to start looking at the work of Verrocchio. I am trying to think of other secular scenes on tombs before this, are there any? Also anything that so marked the life of women and in this case the death of this woman?

LikeLike