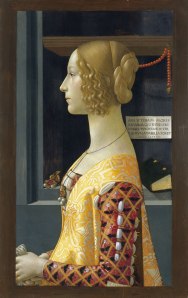

Fig. 1. Domenico Ghirlandaio, Portrait of Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni, 1488, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid.

Pregnancy was a dangerous event in the life of a fifteenth-century Florentine patrician woman. One-fifth of all deaths among females that occurred in Florence during this period were in fact related to complications in childbirth or ensuing post-partum infections. In the years 1424-25 and 1430, the Books of the Dead recorded the deaths of fifty-two women as a result of labour. As conditions for pregnant women did not improve in the ensuing half a century, childbirth remained a dangerous event for women to endure. Husbands took many precautions to ensure a successful birth as can be seen in the vast array of objects associated with this event created at this time. People turned to religion and magic in order to ensure that both the mother and child would survive this perilous process. Death in childbirth affected women from all classes and wealth did not act as a deterrent. The loss of a fertile young woman was detrimental to both her family and to society in general. Not only did her natal and conjugal families lose out on the children she may have had in the future, the loss of the child that she carried (which was commonplace) denied the family the opportunity to forge advantageous marriage alliances and heirs to the family name and wealth.

In a society which had recently experienced the devastating effects of the Black Death, leading to the loss of approximately 80,000 of its citizens, the civic authorities of the city-state began to actively promote the need for the production of children to counter-act the dramatic population decline. A family-centred ideology emerged at the core of Florentine society. In the writings of resident authors such as Leon Battista Alberti, marriage and family were regarded as the building blocks of a strong and prosperous society. The need for children was of paramount importance to the citizens of Florence as a means of ensuring the continuation of family lineages and the prosperity of the society which they were born into. The production of children was thus perceived primarily as for the good of both the family and society rather than just for individual satisfaction. The inhabitants of the city-state and particularly the women were under immense societal pressure to carry out their civic duty by producing offspring. As women were the bearers of children, their roles within their marital families centred upon their ability to fulfil the role of motherhood and produce as many children as possible for their husbands.

A number of art works dedicated to women who died in childbirth survive to the present day and Ghirlandaio’s Portrait of Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni dating from c.1488 is one of the most famous examples [Fig.1]. It is clear through the examination of these art works that a woman received a privileged status through her death in childbirth, particularly if she had already provided her husband with a male heir. Although the depictions of women who died in this manner do not usually reference what caused their demise, these works promote motherhood to contemporary Italian viewers in a number of ways. This argument stems from an idea put forward by the historian David Herlihy who states that, due to motherhood, Renaissance Italian women were elevated in status.[1] The following brief synopsis of a painted portrait of a Florentine woman demonstrates that, within the context of the republican city-state, a woman was clearly defined by her role as mother and contributor to her husband’s dynastic lineage.

Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni

Giovanna was born into one of the most influential and powerful families of the period, the Albizzi. At the age of eighteen, Giovanna entered into another powerful Florentine family, the Tornabuoni, through her marriage to Lorenzo Tornabuoni. Marriage was the key event in the lives of Florentine citizens, particularly for women as they were dependent upon matrimony alone to define their status. Girls were conditioned for their nuptials from an early age. The similarities in the ages of the bride and groom is considered unusual in the Florentine context; usually the man would choose his bride when he was twenty to twenty-five years old and, if he should feel that his position would improve, he would wait until he reached thirty to marry. The bride was usually in her early teenage years at the time of betrothal. Gert Jan van der Sman argues that the similarity in their age suggests that their union was for dynastic purposes.[2] On 11th October 1487, Giovanna successfully gave birth to her first child, a boy who was named Giovanni after his grandfather, the family patriarch. Giovanna died less than a year later on 7th October 1488, as a result of childbirth. Of particular interest are the series of images created by the prominent Florentine artist Domenico Ghirlandaio commissioned by her grieving husband and also her father-in-law shortly after her death.

Ghirlandaio’s Portrait

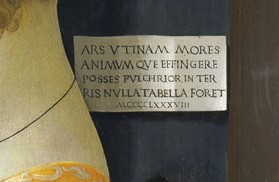

The Portrait of Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni dating from 1488 includes a number of interesting elements such as the Latin epigram. It reads as:

‘Ars Utinam Mores Animum que Effingere Posses Pulchrior In Terris Nulla Tabella Foret’

[Art, if only you were able to portray character and soul, no painting on earth would be more beautiful]

The identity of the author of these words has been a matter of much contention amongst art historians. Maria DePrano presents the most relevant interpretation and identification of the true author of the verse by arguing that it was Lorenzo’s composition which had been based upon an epigram written by the ancient Roman poet Martial with a minor change in the verb conjugation to make the words more personalised.[3] Lorenzo verbalises his sorrow over the sudden death of his wife. Not only did he lose his beloved wife who he had been married to for only a brief period of time, he also lost the child which she was giving birth to. Their first-born son, Giovanni, who was less than a year old at the time of her death, lost his mother. Therefore the epigram is one of both anguish and lament by a grief-stricken husband beseeching art to bring his wife back to life. The position of the inscription within the portrait itself is interesting and deliberate on the part of the artist as the bottom left hand corner is partially obscured by the sitter’s beautifully elongated neck. The viewer is left in no doubt that the words of this epigram are in fact referring to Giovanna herself, her character, mind and feminine virtues. It is important to note that the majority of inscriptions included in the portraiture of Florentine women were located on the reverse side of the images such as Leonardo da Vinci’s Portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci c.1474-78 [Fig. 2] Their placement on the reverse suggests that they were intended to be viewed by a select private audience such as the patron who commissioned the work and close family. In the case of Ghirlandaio’s portrait, the inscription’s prominence within the work itself must be interpreted as a public statement, intended to be viewed by a wider audience.

Fig. 2. Leonardo da Vinci, Portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci, c.1474-78, National Gallery of Art, Washington

The open nature of this personal statement of Lorenzo’s lament is furthered by the work’s original location. This image is one of the only female portraits of the Renaissance period whose exact location was documented in an inventory. It was located in Lorenzo’s personal chambers in the chamera del palcho d’oro (‘chamber with the gold ceiling’) of the Palazzo Tornabuoni and hung in this room for nearly ten years after her death when Lorenzo had in fact remarried.[4] The private chambers of Florentine patrician men were quasi-public spaces within the palazzo and the camera was in fact the most controlled space, only accessible to those who were admitted to the space by its owner. Those who saw the portrait would have been invited by Lorenzo himself into the room. It was within these spaces that men placed their most valuable art works and prized possessions so that their wealth and prestige could be exhibited and seen. By placing Giovanna’s portrait in this chamber, Lorenzo not only gave Giovanna a prized position within his household but simultaneously suggested that her image and thus Giovanna herself was in fact a cherished possession of his. The inscription acts as a public acknowledgement of her worth and significance to her husband and adds to the sense of high regard she achieved posthumously.

The significance of physical appearance in female portraiture

The manner in which Ghirlandaio represents his sitter including the profile format and her appearance added to the perception of her privileged status within the Tornabuoni family. In classical times, the use of the strict profile pose was allied to biography so that these portraits came to stand for their sitters’ virtuous behaviour. Its use in Florentine art asserted similar virtues upon those represented. With her eyes and face averted, Giovanna’s depiction was particularly apt in a society which idealised the images of women in terms of their chastity and modesty. Her upright posture emphasised through the pose demonstrates her chaste nature, considered the most fundamental virtue for a patrician woman to possess as it was deemed vital to ensure the legitimacy of the offspring she produced. It also allowed the viewer to appreciate Giovanna’s beauty, as the observer can clearly see her domed forehead, elongated neck and high hairline, features considered beautiful in Florentine society. Beauty was regarded as another significant quality for women to possess which was clearly emphasised by its reference in the portrait’s inscription.

The domestic environment was seen as the space reserved for women and Jacqueline Marie Musacchio points out that many Florentine women spent a large portion of their lives being controlled by male family members and contained within the walls of the family palazzo.[5] Alberti argued that it was in fact natural for a woman to remain inside and to tend to the household while the man’s place was outside the home, tending to all other matters. In a culture which believed that a woman should give the impression that her body was contained and protected with her limbs controlled, the use of the profile in female portraiture was perfectly suited to demonstrate this ideal.[6] This is furthered by Giovanna’s physical containment within the confines of the Netherlandish motif of the dark tomb-like niche.[7] Therefore Giovanna is shown here as exemplary and virtuous in the 1488 portrait.

Giovanna’s pose and appearance also held importance with regards to the exhibition of the wealth and prestige of her marital family. Extravagant costumes and jewellery were symbols of affluence and status in this society. The dominance of the initial ‘L’ on the sleeve of Giovanna’s giornea (dress) refers to her husband and thus denotes her as Lorenzo’s wife. The use of heraldic or familial devices on women’s clothing demonstrates how women were perceived in terms of their families- firstly their father’s and then, through marriage, their husband’s. A woman was thus never viewed as an individual with a separate identity who earned honour for their own merits, but was only seen in terms of her ability to assist in the continuation of the patriarchal lineage of the family.

Each of the objects included in the portrait were carefully chosen to provide a further insight into the sitter’s personality and nature which the artist could not evoke in the portrait. The prayer book symbolised the piety Giovanna possessed and the string of coral beads alluded to the use of talismanic objects to safeguard the wellbeing and health of the new born child. Of particular interest is the dragon pendant with its reference to the symbol of St. Margaret, the patron saint of childbirth, to whom women in labour prayed to ensure a safe delivery. The dragon pendant is an unusual inclusion as no other example of such a necklace has been found in a Quattrocento female portrait. The incorporation of the coral beads and dragon necklace in particular subtly allude to the circumstances surrounding her death. The artist successfully constructed an image of Giovanna as a paradigm for the ideals a woman was expected to possess and an exemplar which other women should aspire to imitate in their own lives.

Giovanna’s fate was shared by many of her contemporaries, including her closest female kin. Her mother, Caterina Soderini, mother-in-law Francesca Pitti Tornabuoni, and sister-in-law Ludovica, all died as a result of childbirth, demonstrating the devastating effects of this event on Florentine families. The emphasis on the commemoration of Giovanna in the painted portrait by Ghirlandaio expresses how she was perceived as having played a crucial role in this family in ensuring its continuation and was thus regarded as a valued member due to her role as the mother of the Tornabuoni male heir. Lorenzo, through the medium of art, venerated his spouse for her achievements as a woman through the realisation of her civic duty as a wife. To commission a painted portrait of an individual at this time was to commemorate the sitter for their accomplishments, confirmed in the writings of Alberti who asserted that: ‘Through painting the faces of the dead go on living for a very long time’.[8] Accordingly, Giovanna was commemorated for posterity as an exemplar amongst her sex, the highest of accolades.

[1] D. Herlihy, ‘The Natural History of Medieval Women’ in D. Herlihy, Women, Family and Society in Medieval Europe: Historical Essays, 1978-1991, ed. A. Molho, Berghahn Books, Providence, 1991, 53.

[2] Gert van der Sman, Lorenzo and Giovanna: Timeless Art and Fleeting Lives in Renaissance Florence, trans. By D. Webb, Madragora, Florence, 2010, 29.

[3] Maria DePrano, ‘No Painting on Earth would be more beautiful’: an analysis of Giovanna degli Albizzi’s portrait inscription’, Renaissance Studies, Vol. 22, No. 5, 2008, 632-33.

[4] Ibid, 634.

[5] Jacqueline Marie Musacchio, Art, Marriage and Family in the Florentine Renaissance Palace, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2008, 62.

[6] L.B. Alberti, The Family in Renaissance Florence, Waveland Press, Illinois, 2004, 207-8.

[7] J. Woods-Marsden, ‘Portraits of the Lady, 1430-1520’, in D.A. Brown (ed.), Virtue and Beauty Leonardo’s Ginevra de’ Benci and Renaissance Portraits of Women, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford, 2001, 69.

[8] L.B. Alberti, On Painting and Sculpture, trans. C. Grayson, Phaidon, London, 1972, 60.